The scale of new equity investment that is being deployed in the affordable housing sector shows no sign of abating; research published by Savills in 2021 suggested that at least £23bn might be deployed by 2026.

At the same time as new equity investment arrives in the sector, the traditional housing sector faces well documented headwinds to maintain its development "run rate"; as we are all aware, associations are having to make very difficult decisions about the allocation of capital into new build programmes as compared to investment in existing stock- not least because of the huge challenges in funding building safety works and the move towards net zero.

So how can associations maintain a development pipeline in these challenging times?.

In my mind, a substantial part of the answer must be collaboration between traditional housing associations and new equity investors. Indeed recent research published by Legal & General and the British Property Federation demonstrates that the only way of achieving affordable housing delivery of 145,000 dwellings a year is by harnessing the power of equity investment.

Equity investment and partnership working can come in many shapes and forms, and part of the challenge for boards and executive teams alike is to understand the models that are available and to work through what approach might suit them best. Our teams here at Trowers are already working delivering these models at scale, and over the course of the next few editions of Quarterly Housing Update expert colleagues will look at the various models that are being deployed in the sector.

We start the series by looking at joint ventures between traditional housing associations and equity investors. Clearly joint ventures are nothing new for the housing association sector and there is already a wealth of good practice that associations can build on in how to establish and operate joint ventures and to settle on an appropriate balance of risk and reward in structuring these models.

What is different about the concept of a joint venture between a housing association and a For Profit Registered Provider (FPRP) is the flexibility that such a model might offer once the dwellings have been completed; in a conventional joint venture between a developer and a housing association the completed affordable housing stock is more often than not transferred back to the housing association joint venture partner. Whilst this clearly reduces the risk to the housing association during the development phase (and during the sales phase if the development involves the sale of properties on the open market) the model remains constrained by the housing association's own balance sheet (in other words there is a finite capacity for the association to acquire new stock- whether that be from a joint venture or otherwise).

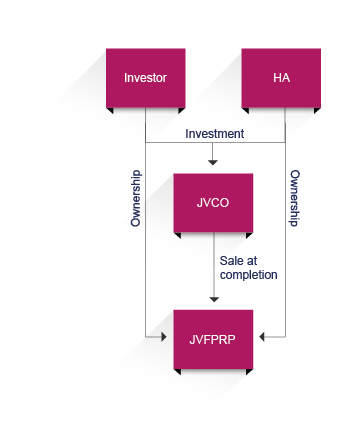

Under a joint venture with an FPRP the parties have the choice about where completed stock sits at completion; indeed the model doesn’t necessarily require a definitive decision on the ownership of the stock at the outset of the joint venture- there may well be flexibility built in that ordinarily has stock being acquired by the FPRP but that allows (for example) an association the option to acquire depending on the financial capacity of the association at the relevant time; moreover it might also enable a split of tenures (for example it might be that shared ownership stock is owned by the FPRP whilst rental tenures are owned by the housing association). This model enables the development joint venture to achieve greater scale because the offtake at completion isn’t constrained. This is shown in a diagrammatic form below.

For the housing association this model allows their development team to continue to operate at scale notwithstanding the possible diversion of financial resources to invest in existing stock; it also enables the housing association to be retained as housing manager for the entirety of the scheme so that from a customer experience perspective, the standard of housing management would be the same regardless of who their landlord was.

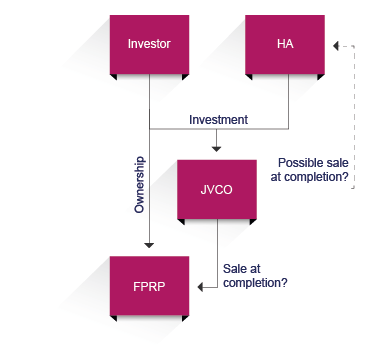

So where might this model go next? The obvious conclusion (and we are working on such a project as we write this article) is to extend the joint venture to the landlord role, so that a housing association forms a FPRP in partnership with an equity investor as shown below. Not only would this model bring with it all of the advantages outlined elsewhere in this article, but it forges a genuine long term partnership that gives the association a long term stake in the new properties. For many associations this form of partnership could offer a real alternative to merger and may well enable them to "stay local" (or in the case of specialist providers – for example in the later living or in extra care sectors) to scale up their development.